This piece picks up Heidegger’s Lichtung—the clearing—from the first essay on Nosferatu and substance-dependent cinema, tracing its relevance in an entirely new context.

IT HAS BECOME, somehow, gauche to try to talk about capitalism. I hate to admit this. I don’t know when it happened, or how. One moment, Mark Fisher was killing himself, and Repeater Books was publishing K-Punk, the tome of the decade, or so it seemed. A friend of mine wore a CCRU t-shirt and a JSTOR ball cap at a wine hang in Tempelhofer Feld in 2019. She couldn’t have foreseen that no one was going to be lugging around a 800-page collection of blog posts and an unfinished, speculative fulmination of capitalism called Acid Communism—an essay urging us to rediscover the communal psychedelic potential of the ’60s and ’70s before it was swallowed whole by the banal individualism of New Ageism.

By now, we have become too absorbed in our selfhood for all that. If we talk about systems at all, it is only to identify the ones preventing us from living out our impulses as freely, as frictionlessly, as we believe we deserve.

Before it disappeared—collapsed in on itself like a dying star—discourse around capitalism had already been embalmed, anesthetized, its radical charge neutralized by the same forces it sought to critique. Packaged into leftist publishing cycles, meme accounts, and vague gestures toward accelerationism, it lost its urgency, its stakes. The grandiose failures of Crypto and Web3 played out like a Fisherian farce. Alternative economies, promising freedom from capital’s grasp, were only ever hyper-capitalist grifts that accelerated its logic rather than rupturing it. What once animated early techno-materialist paranoia has since dissolved into NFT auction houses, ironic proximity to God and politics, and Lacan.

Why, exactly, is it embarrassing to speak about capitalism?

Is it that we are so fully entrenched in its logic that to name it at all feels clumsy, childish—like a baby in a stage of object permanence, newly aware of the fixtures that compose reality? Fisher, in Capitalist Realism, called it an atmosphere—“not a particular type of realism,” but something more pervasive, more total. Not an ideology one could oppose, exactly, but the air itself. The world as it is. Unlike fascism or other twentieth-century systems that demanded explicit allegiance or rejection, capitalism is insidious because it does not require belief. Only participation. And exhaustion.

✴︎

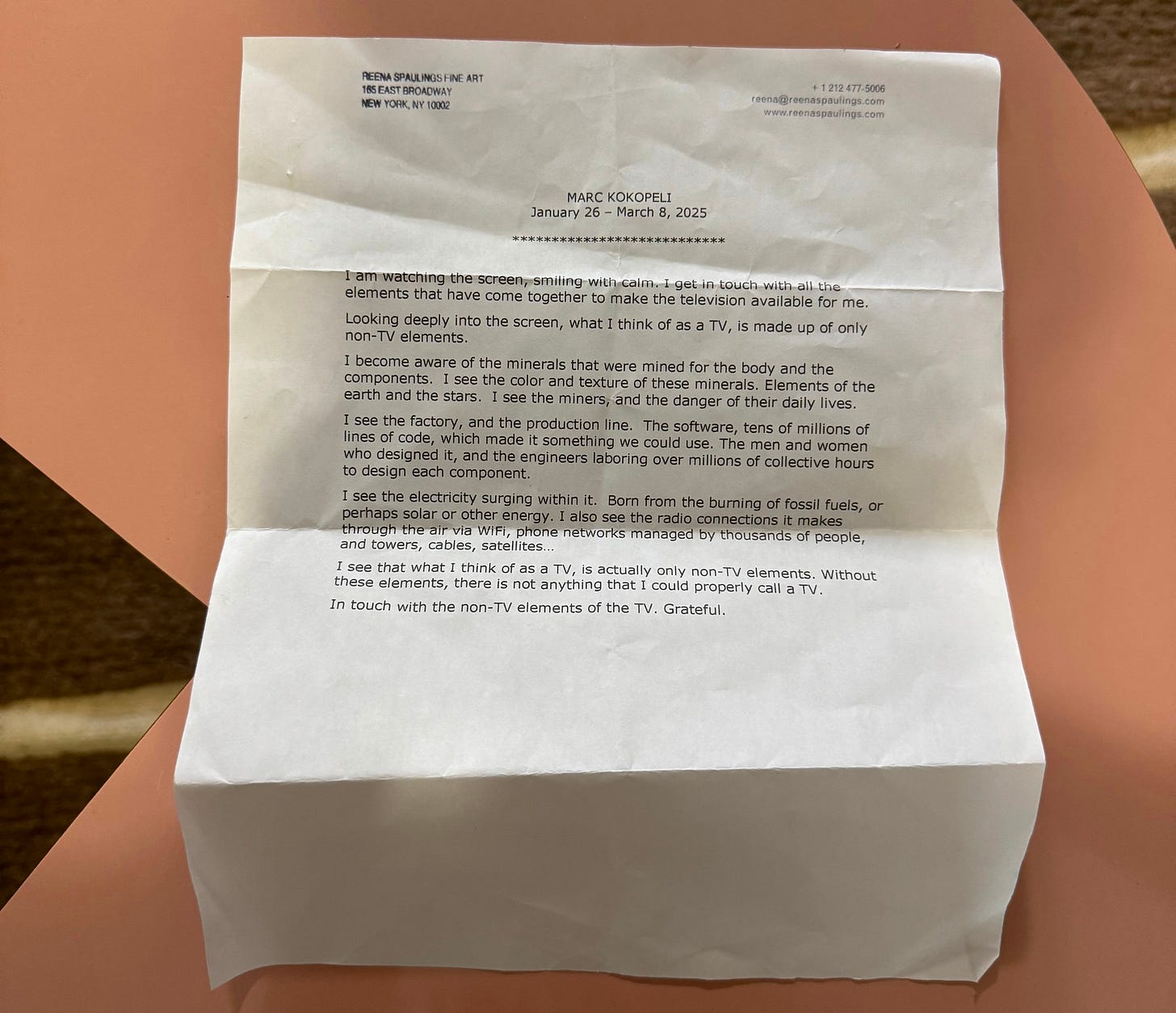

So when I see Marc Kokopeli drop the phrase “factory and production line” in the press release for My TV Show I ❤️ TV up now at Reena Spaulings, I’m slightly taken aback. Reena, once defiantly anti-institutional, now reads as something else—more detached, more abstracted. The politics are still there, maybe, but blurred. A posture rather than a position. Still present, but harder to pin down.

That shift was obvious at the opening. Downtown scenesters, artists, writers—the usual crowd, hovering somewhere between relevance and spectacle. The show itself was an event, a gathering. About presence as much as work. In this context, Kokopeli’s invocation of the production line feels anachronistic, a relic from a time when critique was direct, maybe even sincere. Here, it lands differently. Not as indictment but as a gesture, a knowing nod. A phrase dropped in quotation marks, more wry than urgent.

Which is, probably, the point. What it gestures toward is not just capitalism, but our whole relationship to the future. The way it’s all become tongue-in-cheek—Oh, those layoffs. Oh, that apocalypse. 10 steps to survive Monday and the end of the world. The future, once a real thing, apprehendable, something to work toward or against, is just another punchline.

There was a time, in postwar America, when the future had structure. When Ayn Rand could claim, with absolute conviction, that individual success was simply a matter of will: “The question isn’t who is going to let me; it’s who is going to stop me.” Then, causality was intact. One thing led to another. The past, present, and future fit into a sequence, a story. Now, that sequence is broken. Time flickers, collapses. The future, like capitalism itself, is something we no longer quite believe in, yet still operate within.

“The slow cancellation of the future has been accompanied by a deflation of expectations,” Fisher writes in Capitalist Realism. This is what Kokopeli captures in his ready-made TVs—not just lost futurity, but the mechanisms of its disappearance.

✴︎

Let me digress.

In the winter months, I have been averaging six miles a day, which is roughly 13.5K steps—exceeding the recommended 10K, though I don’t know who recommends this or why. Every Sunday, my phone delivers a report on how many hours I have spent looking at it. This week: four hours a day. I have no baseline to compare this to, but I suspect it is too much. My phone, I note, is quite generous with its calculations. It tracks everything—Gmail, Messages, Instagram, Substack. Am I meant to capitalize these names as if they were beloved friends?

What am I supposed to do with this information? Is my phone telling me to use it less? It is hard to believe that a product would monitor a unit that, in theory, would justify its obsolescence. Maybe this is a psychological trick—by making me aware of these numbers, my usage becomes remote to me, harder to regulate, harder to stop. I believe this is called “reverse psychology.”

Screen time is a joke, a self-parody. A reminder that we quantify our lives as though measurement will offer control. But as the Einstein quote goes, “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.” There is something futile about it—breaking the world into units, believing they will add up to something. Capitalism has trained us to think this way, to believe that tracking is knowing, that knowing is mastery. But entropy is still there. The counting will not save us.

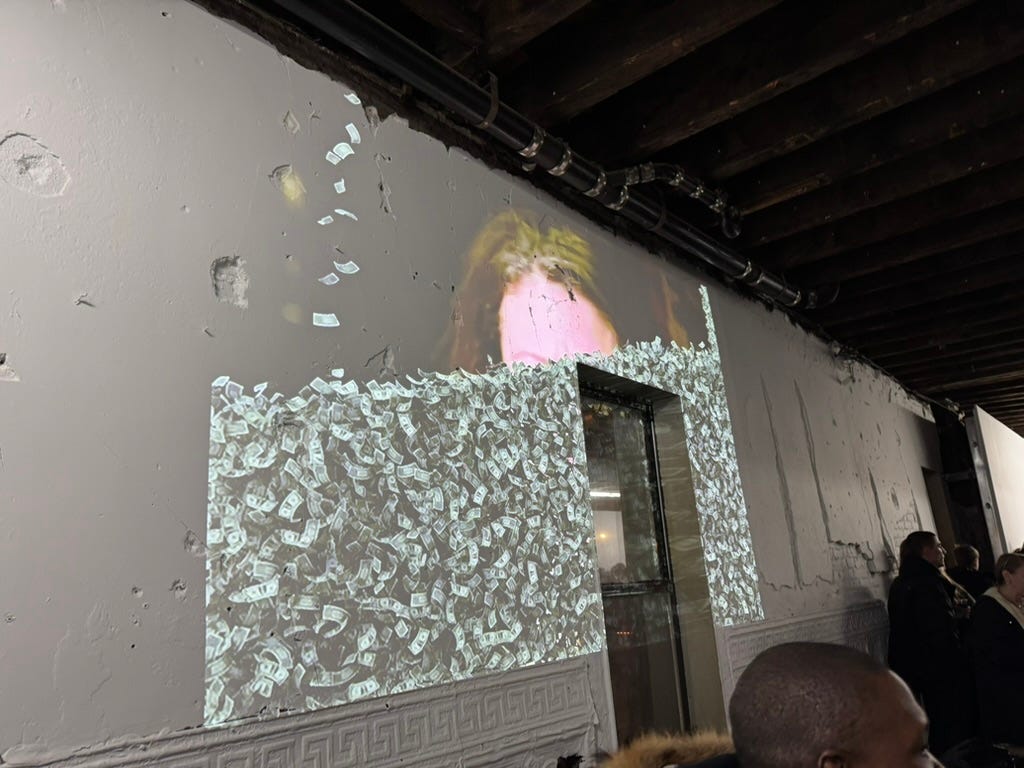

This tension—between measurement and meaning, between data and disappearance—is what animates My TV Show I ❤️ TV. Kokopeli writes in the press release (which, as I learned at John Kelsey’s reading at Artist’s Space, is based on a Buddhist prayer): “What I think of as a TV is made up of only non-TV elements.” Near the entrance of the gallery, a projection loops an old screensaver—dollar bills stacking, accumulating endlessly over video footage from Ken Burns’ 17-hour documentary on New York City. I’ve seen this piece before, or something like it, three years ago in Berlin at The Wig.

Then, as now, the image of capital accumulating against a nostalgic backdrop felt both absurd and inevitable. In that earlier work, which reappears in this show, an animated elephant drags bricks across the screen, while the same Burns documentary plays in the background. Capital and labor, circulation and weight, a loop without resolution.

The screensavers, once passive digital artifacts meant to prevent burn-in, now take on a sharper, more deliberate significance. Their looping, hypnotic motion mimics the way capitalism functions—an invisible, self-sustaining system, indefinitely extending itself. Superimposed over Burns’ polished, sentimentalized retelling of American history, the effect is both absurd and inevitable. Burns, who structures his documentaries as sweeping, authoritative narratives of progress and struggle, here finds his vision compressed under the weight of accumulation itself—history reduced to another aesthetic backdrop.

A nostalgic, PBS-brand framing layered over the banal, pre-programmed animations of a lost desktop era. The collision of these two visual languages—the earnest, mythic American past and the automated, digital afterlife of capital—reveals what is already apparent. Capital does not just erase the future; it absorbs the past, hollowing out both history and progress until neither has any weight at all.

It is hard to imagine Kokopeli has not read Capitalist Realism, where Fisher writes: “The 21st century is littered with the relics of an imagined future that never arrived.” This is precisely the terrain of My TV Show I ❤️ TV.

Beyond the screensaver works, Kokopeli has assembled a dozen or so screen-like devices—though one could hardly call them TVs—from the 2000s and 2010s. Objects like the two red plastic orbs concealing an internal screen in “Check It Out,” or the mini High School Musical locker-screen in “Facing Up,” are relics of an era when technology fully embraced kitsch. These were objects made not for function but for play, electronics that disguised themselves as eggs, apples, or miniature pop-culture shrines. A moment when consumer electronics briefly flirted with something other than strict utility—gesture, decoration, self-expression. A kind of object-oriented utopianism, if one were being generous.

This transformation—from functional to decorative to obsolete—is best understood through Heidegger’s distinction between ready-at-hand and present-at-hand. Something is ready-at-hand when it is seamlessly integrated into life, unnoticed in its usefulness—a keyboard beneath one’s fingers, a refrigerator one opens without thought. The moment it breaks, it becomes present-at-hand—an object to be scrutinized, evaluated, regarded as an object rather than an extension of use. The screens in My TV Show I ❤️ TV have already undergone this shift. Once designed to be integrated into daily life, they are now displayed as artifacts, stripped of function, their presence conspicuous, unresolved.

The press release echoes this present-at-hand awareness: “I see the electricity surging within it. Born from the burning of fossil fuels, or perhaps solar or other energy. I also see the radio connections it makes through the air via WiFi, phone networks managed by thousands of people, and towers, cables, satellites…” A screen that sits on a plushy plinth, reduced to the sum of its material components.

Most disorienting are the transparent LCD cabinets, perhaps the most direct enactment of Kokopeli’s lost futurity. The front panels of these display boxes have been replaced with transparent glass. Inside, a single cinder block sits motionless while video plays directly on the glass surface. The effect is immediate dissonance—we crouch, tilt our heads, expecting to perceive depth or a visual trick that never materializes. A screen, by design, is meant to disappear in function; here, it refuses. Instead, it obstructs. The expectation of seamless transmission—of effortless image, immediate meaning—is entirely denied.

There is a brief, almost frustrating moment where one treats the glass as a normal window before realizing it is the screen itself. It is this moment of hesitation, of misrecognition, that reinforces the uncanniness of Kokopeli’s objects. These were once intended as futuristic technologies; now, they are post-function. Neither integrated nor defunct, but stuck in a liminal space between past and future: too futuristic for their time, too outdated for ours.

Like much of Kokopeli’s work, they expose the failure of capitalist realism’s promise of perpetual innovation. Objects designed to integrate seamlessly into the world, now stranded in aesthetic limbo—looping, suspended, awaiting a function that will never come.

✴︎

Kokopeli’s work—his use of commercial remnants—falls in line with the ready-made. The ready-made, which was always a kind of irritation, a slight against function, a repurposing, but not exactly an elevation. The object is taken out of its system. A toilet, a urinal, a bicycle wheel. Its utility neutralized, its context altered, it becomes, suddenly, art. Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), the obvious example. A urinal, mass-produced, now useless in a different way. Not broken, not discarded, but relocated. Suspended outside of circulation.

By the time Warhol got to Brillo Boxes (1964), the shift had already happened. The logic of the ready-made had been folded back into capital. It was no longer about rupture, but exposure. A kind of re-enactment of capitalism’s own trick: to strip objects of use, to make them valuable by sheer repetition, visibility, context.

Kokopeli’s screens inherit this history, but differently. They were supposed to be cutting-edge, but they never fully arrived. It is not just that they are functionless now—it is that they were never quite functional to begin with. Objects meant to fit seamlessly into the logic of consumer tech, and yet, somehow, left out of it. Their transformation into art does not imbue them with new meaning. It only confirms their failure to ever mean anything else. Suddenly visible, suddenly objects again. They do not function. They only persist.

Inside the transparent LCD cabinets, a cinder block. A screen is meant to project, to transmit, to create a virtual space beyond itself. Here, it only reinforces what is already there: weight, material, brute presence. An object containing another object, displaying nothing but its own vacancy.

The most unsettling thing about Kokopeli’s work is that it does not pretend visibility is an answer. This is the problem with late capitalism. It has made all of its failures obvious, inescapable, fully documented. That does not stop them from continuing. Fisher understood this: “The ruling class has lost the ability to rule. But the ruled still lack the ability to take power.”

And so, the loop. I recognize the absurdity of tracking my own consumption. I do it anyway. I check the numbers. I check them again. I wait for them to tell me something. They don’t. The system does not require belief. It continues, through sheer momentum.

✴︎

Fisher, borrowing from Jameson and Žižek, wrote: “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.” It has become a cliché. A kind of joke, a tired refrain, except that it is also true. Capitalism’s failures are omnipresent, visible to the point of exhaustion, and yet, its logic remains intact. The system sustains itself through collapse, through crisis. The possibility of an outside—of anything beyond—seems to recede further with each repetition.

Kokopeli captures this, a world where capitalism continues to produce long after it has stopped producing anything new. The future, or what we once thought of as the future, stalled. The loop, infinite. But is there an exit? A rupture? If so, it does not seem to come through critique alone. This is where Mark Leckey diverges.

Leckey’s 3 Songs from the Liver at Gladstone does not document failure so much as it tries to break free from it. His work is not about dead screens, obsolescence, or the impossibility of futurity. It is about something else—about sensation, intensity, the body. It is not critique; it is something more immediate. If Kokopeli’s objects demand analysis, Leckey’s demand engagement. They do not ask you to think; they ask you to feel.

Leckey describes his three “songs” as coming not from the heart, not from the intellect, but from the liver. An odd, deliberate choice. The liver, unlike the heart, unlike the brain, is not sentimental, not rational. It does not contain; it processes. It absorbs, filters, metabolizes. It does not reflect; it acts.

Before modern medicine, before the clean division between organs and their functions, the liver was thought to be a site of vision. A screen of sorts. In Mesopotamian and Roman traditions, haruspicy—the reading of livers—was a way of seeing, of glimpsing something beyond what could yet be understood. The liver, an instrument of divination. A record of what has passed, and what is still to come.

This is where Leckey veers from Kokopeli. Kokopeli’s screens are artifacts of a world where capitalist realism has already sealed off the future. His work lingers in the wreckage, documenting failure. Leckey, by contrast, is looking for something else. Not critique, not resignation, but a way out—through altered states, sensory overload, the sheer force of bodily experience. If Fisher argued that capitalist realism is an all-encompassing atmosphere, one that suffocates the possibility of alternatives, Leckey suggests that rupture is not conceptual but metabolic. It does not happen through thought or theory, but through the body in its immersion, excess, ecstatic destabilization.

✴︎

In “To the Old World (Thank You for the Use of Your Body),” Leckey takes a viral video—a drunken lad crashing through the glass of a bus stop—and reframes it as an ecstatic event, a moment of involuntary transcendence. In 2022, at Under Under (Galerie Buchholz, Berlin), his work functioned similarly, collapsing the specificity of place into a kind of portal. Here, too, the bus stop is reconstructed exactly, orange benches intact, a perfect recreation. The viral footage plays in loops, variations of the same event, the man passing through—except this time, something shifts. The glass is not just breaking. It is opening. He does not just crash; he enters, slips into other dimensions. The screens—like the advertisements that usually occupy these bus stops—begin to show something else.

In “Mercy I Cry City,” Leckey cuts rectangular openings into the walls of the gallery. At first, they are empty. Then, darkness. Then, suddenly, a screen illuminates the space beyond, revealing a 3D-rendered castle. The room next door is no longer the room next door. The gold-leaf edges of the holes recall Byzantine icons, and this reference is deliberate. A Byzantine icon, unlike a screen, is not meant to be looked at but looked through. It is not an image; it is a passage. Leckey is seeing beyond the screen, beyond the TV elements

In his press release, Leckey speaks of exultation—“to leap up” or “to leap out.” A kind of engagement that bypasses cognition, that operates on a bodily level, where thought is irrelevant, where perception is flooded, overridden. He describes a moment, pushing a pram through a park in lockdown, when the sun broke suddenly through the clouds, music flaring in his ears, and he felt it: a “tremendous muchness, an excess of everything.” This is what he is after—not critique, not reflection, but the sheer force of experience.

Where Kokopeli makes failure visible, Leckey refuses to linger in it. He does not document capitalism’s wreckage; he tries to step through it. If capitalism has made it impossible to imagine alternatives, then perhaps the only way forward is to feel our way out—to find intensity, disorientation, states that overwhelm and distort the rigid contours of the present.

✴︎

Fisher’s essay “Baroque Sunbursts” offers a way into this. He understood rave not just as subculture, but as rupture. A collective intensity, an ecstatic event, the dissolution of the privatized self. This was why the Tory government cracked down on raves in the 1990s—not because they were political in any explicit way, but because they were collective. Because they threatened the atomized, individuated subject on which capitalism depends.

“The campaign against rave might have been draconian,” Fisher wrote, “but it was not absurd or arbitrary. Very much to the contrary, the attack on rave was part of a systematic process—a process that had begun with the birth of capitalism itself.”

Capitalism survives by eliminating “the specter of a world that could be free.” Rave was dangerous because it proposed another kind of time, another way of being. It broke with enclosures—the work cycle, the segmentation of leisure, the division of subject and environment. Capitalism replaces collectivity with the ideology of hard work, individual responsibility, and isolated consumption. Rave rejected all of this. It allowed for duration without structure, sensation without purpose, euphoria without productivity.

Leckey’s work tries to reactivate this threat. Not through nostalgia, not through representation, but through immersion. He is not documenting a lost future; he is reaching for a break, a tear, a way through. His use of sound, repetition, excess—all of it mirrors Fisher’s vision of rave as a post-capitalist potential. Time unravels, labor and rest collapse, the individual dissolves into rhythm, the body is not a site of exhaustion but of transformation.

This is where Heidegger’s Lichtung—the clearing—comes in. A space where being becomes visible, where truth, briefly, steps out of concealment. Capitalist realism, by contrast, is enclosure. A sealed atmosphere, a system so totalizing that nothing new can break through. But rave—like Leckey’s work—suggests that the clearing does not have to be a political event. It can be metabolic. It can happen in the body. The liver, in this sense, is its own clearing—a site of transformation, where reality is filtered, absorbed, processed. Where perception, briefly, shifts.

Fisher called rave a baroque sunburst. A flicker in the structure of capitalist realism, a distortion, a glimpse of something else. He quotes Frederic Jameson: “From time to time, like a diseased eyeball in which disturbing flashes of light are perceived or like those baroque sunbursts in which rays from another world suddenly break into this one, we are reminded that Utopia exists and that other systems, other spaces are still possible.”

Leckey’s exultation is this. Not a future, not an alternative, but the sensation that another world—somewhere, somehow—is still possible. Not for long, not as program, but as affect. A moment. An opening.

✴︎

It was only at John Kelsey’s reading last night that I came to understand Kokopeli’s press release more profoundly. It clicked, his work was in its own way, a baroque sunburst, too. His assertion that a TV is made of non-TV elements is a kind of Buddhist prayer—a metaphor for the continuation of the mind after death. Look at blank and see that it is made of not blank. This is the formula for transcending individualist perspectives, for accessing a deeper truth about the universe. “Grateful,” Kokopeli concludes in his press release. A more emotional ending than I expected.

This realization makes me reconsider his stance. What initially seemed wry and critical now feels like something else entirely. Something less aggressive than Leckey’s rupture. Subtle, more closer to love. I think of the big red heart emoji in the show’s title.

“TV is never in the present,” John Kelsey said. We exult ourselves. Information is something we agree upon. A blank is composed of non-blank elements. To see this truth, we must leap out of our perception. The individual is made of the collective.

But I didn’t see this at the opening. I only understood it later, after the director of Reena Spaulings explained the show to me. And if I didn’t grasp it then, surely others didn’t either. Many were drawn to the work for its aesthetic, for its “postability.” The screens were good to post on Instagram—the platform where, as John Kelsey put it, “people say yes or no.”

Were Kokopeli’s TVs not information, then? Is this what makes them art—because they resist a single meaning? That would be too easy a conclusion. I feel exulted when I see good art. But is good art real art? Is good art a clearing?

Is art the liver of society, or the diseased eyeball?

If art is rupture, what do we make of the new dialogue around ruptures? The trends of “opting out,” “slowing down,” “leaving society.” Are we all artists, enacting this ideology of rave, now an algorithmic movement, of screen-free mornings, distraction-free meals, the measured pacing of analog time? A response, supposedly, to the same conditions that make capitalist realism feel totalizing.

To slow down. To go screenless. To be present. These have become bourgeois consumer experiences. Optimized rather than inhabited. And here we are, quantifying our own rejection of quantification, tracking time spent offline as if presence itself were a productivity metric.

But presence, too, is made of non-present elements. Productivity is made of non-productive elements. Critique, likewise, is made of non-critical elements—love, gratitude, those faculties of deep attention and presence. Different from measurement, an antidote to quantification.

✴︎

There is an overlap between “higher” consciousness in yogic traditions and politically “raised” consciousness in the radical movements of the 1970s. Both go back further. Political consciousness comes from the Marxist idea of class consciousness—the moment workers recognize that their collective interests outweigh their personal interests or cultural differences. Meanwhile, the idea of higher (or “elevated,” “universal,” “cosmic”) consciousness is rooted in Hindu and Buddhist traditions, which see the self as an illusion.

Liberation comes from seeing the self as just a fragment of a greater whole—a state sometimes called “enlightenment,” though the original Sanskrit term is more accurately translated as “awakening.” That “woke” would emerge as radical slang for political awareness seems, in this light, obvious.

I once heard someone say that Buddhism would become the dominant spiritual practice under late capitalism because it teaches total acceptance— “religion is the opiate of the people”! There is something unsettling about this. If acceptance is the end goal, does it foreclose radical change? Can one resist if one has already surrendered?

Maybe not. But maybe, in capitalism’s relentless present, the only way to endure is to cultivate a kind of detachment—not as surrender, but as a clearing. A space where another kind of consciousness might still emerge.

And in the clearing, maybe something else is there. Maybe happiness. Gratitude.

~

Really good essay. Loved the step in the argument linking Buddhism's current popularity with today's political doomerism.

i love this series so far